Poor President Trump!

Pour on Those Tweets and We'll Pore Over Them

Oh no! Our Dear Leader is being trolled by some no-account novelist (fake writer!) over his misuse of the word pour in a recent tweet. How unfair of Rowling to expect a busy man like the President to worry over niggling things like grammar and proper usage when communicating his profound thoughts to the waiting world, 140 characters at a time.

And here's the lesson, boys and girls--good editing skills are a necessity for us mere mortals. Great and Powerful Men, like OZ and Trump, may not have to worry about problematic homophones, but the rest of us do, lest our readers think us uneducated and careless. Being able to carefully edit one's own writing for mechanical and usage mistakes is a vital skill that all language arts students must master.

Revision is an important part of the writing process (a step that most students, I find, hate) that will improve the focus and organization of any piece of writing. Editing is the final polishing of the gem--checking for all the little surface mistakes that invariably surface. Revision is certainly the more important of the two, because that's about content; however, readers are very likely to judge writers harshly on surface mistakes because they're easier to identify and smirk at (as opposed to the deeper problems of focus and organization, more difficult to identify clearly, which is why less effective writing teachers focus over much on surface errors and not of the deeper problems).

So, how to help your writing students become better editors? To begin with, they need to know the applicable rules for spelling, punctuation, grammar, usage, and so forth. This means direct instruction of the incredibly boring minutiae of language, but there's no getting around that. Our modern word processors do an amazing job of pointing out many errors, but that's no substitute for careful editing. Then practice: Purdue OWL offers some great on-line instruction and practice; editing classmates' writing is also a good exercise. Students need to get into the habit of reading their work slowly, word for word--they know what they meant to say, but do the words on the paper actually say that?

And as for Mr. Trump's particular error: mixing up similar-sounding words is a common error. English has a great number of homophones and homographs, and it takes direct instruction to make writers aware of them. Take a look at this workbook of homophones and see if it might fit your instructional needs (click onto image):

Geez, I hope there are no errors in this post--that'd be ironic, huh?

Followers

Saturday, July 7, 2018

Thursday, June 28, 2018

The Game's Afoot!

Engaging Young Readers with Mysteries

There's nothing like a good mystery to pull a reader into the story. A whodunit encourages close reading for clues, inferring significance, recognizing character motivation, and hypothesis development and testing. All while engaging young readers with a compelling story. By choosing classic mystery novels, you immediately increase the complexity and rigor of the selection.

My colleague has great results reading Agatha Christie's And Then There Were None with her advanced 8th graders. The reading level is well within the abilities of upper middle school and the kids really seem to enjoy it. And you have the added bonus of leading students on to her other novels, or have reading circles choose another of her novels to follow up.

And of course, there's the grandmaster of all detectives, Sherlock Holmes, who's been quite popular in the movies and on TV lately. I've had great success with The Hound of the Baskervilles--my students really enjoy trying to figure out this moody and atmospheric whodunit. The reading level is more demanding than Christie but still accessible. Of course, you may need to provide some background info on Victorian England, but this might be useful if you segue into another British novel like The Time Machine. If you're intrigued, check out my study guide by clicking onto the image below:

A fun extension activity might be to group students and give them an unfamiliar object, then ask them to glean what information they can by applying Holmes' deductive technique.

Want to really challenge your kiddos? Give them Edgar Allan Poe's Murders in the Rue Morgue--a bizarre account of mayhem and monkey business in Paris. Shorter than a traditional novel, Rue Morgue presents high school students with complex language and inexplicable clues, neither of which is enough to stump the remarkable Auguste Dupin, the very first literary detective. Here's a link to my study guide:

Engaging Young Readers with Mysteries

My colleague has great results reading Agatha Christie's And Then There Were None with her advanced 8th graders. The reading level is well within the abilities of upper middle school and the kids really seem to enjoy it. And you have the added bonus of leading students on to her other novels, or have reading circles choose another of her novels to follow up.

And of course, there's the grandmaster of all detectives, Sherlock Holmes, who's been quite popular in the movies and on TV lately. I've had great success with The Hound of the Baskervilles--my students really enjoy trying to figure out this moody and atmospheric whodunit. The reading level is more demanding than Christie but still accessible. Of course, you may need to provide some background info on Victorian England, but this might be useful if you segue into another British novel like The Time Machine. If you're intrigued, check out my study guide by clicking onto the image below:

A fun extension activity might be to group students and give them an unfamiliar object, then ask them to glean what information they can by applying Holmes' deductive technique.

Want to really challenge your kiddos? Give them Edgar Allan Poe's Murders in the Rue Morgue--a bizarre account of mayhem and monkey business in Paris. Shorter than a traditional novel, Rue Morgue presents high school students with complex language and inexplicable clues, neither of which is enough to stump the remarkable Auguste Dupin, the very first literary detective. Here's a link to my study guide:

Are you already planning your reading program for the up-coming school year? Fire your students up about reading by introducing them to some of the greatest classic mysteries on your classroom shelf.Tuesday, June 12, 2018

Sad Monsters Are Sad

Classic Horror in the Classroom

Most of us like a good scare; I find this to be true of my middle school students. Many of them are reading Stephen King and Clive Barker on their own; the zombie-themed Enemy series by Charlie Higson and The Monstrumologist by Rick Yancey are popular young adult fare, so why not incorporate the genre into your reading and literature curriculum.

One interesting theme to explore with students is the plight of monster--a pitiable figure, as characterized by Mary Shelley in the classic Frankenstein. He just wants to be loved by his creator, who's a total dick to the anguished creature. Granted, it's a tough read (Shelley's prose is pretty turgid and the level of sentimentality is cringy), but older, proficient readers can tackle it. Another compelling classic is Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; the writing is better and will generate great class discussions about the nature of good and bad. Talk about complex texts! They also present excellent opportunities to compare the original texts with popular movie retellings. Click onto the image below for a potential study guide:

If you're willing to slog into murkier candidates, how about Lovecraft's Reanimator? A novella separated into six mini-chapters, it's more gruesome and vivid than Shelley's and Stevenson's classics (I had one child opt out because it was just too scary for her), which might well improve interest and compliance in your audience. Much like Frankenstein, the mad scientist is caught off guard by the consequences of his attempt to play God. I use it as an exercise in getting students to locate and elaborate on textual evidence (a skill most lacking in their essays). Check out my study guide:

Get your kids reading and thinking in the coming school year with a dose of good old fashioned horror!

Classic Horror in the Classroom

Most of us like a good scare; I find this to be true of my middle school students. Many of them are reading Stephen King and Clive Barker on their own; the zombie-themed Enemy series by Charlie Higson and The Monstrumologist by Rick Yancey are popular young adult fare, so why not incorporate the genre into your reading and literature curriculum.

One interesting theme to explore with students is the plight of monster--a pitiable figure, as characterized by Mary Shelley in the classic Frankenstein. He just wants to be loved by his creator, who's a total dick to the anguished creature. Granted, it's a tough read (Shelley's prose is pretty turgid and the level of sentimentality is cringy), but older, proficient readers can tackle it. Another compelling classic is Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde; the writing is better and will generate great class discussions about the nature of good and bad. Talk about complex texts! They also present excellent opportunities to compare the original texts with popular movie retellings. Click onto the image below for a potential study guide:

If you're willing to slog into murkier candidates, how about Lovecraft's Reanimator? A novella separated into six mini-chapters, it's more gruesome and vivid than Shelley's and Stevenson's classics (I had one child opt out because it was just too scary for her), which might well improve interest and compliance in your audience. Much like Frankenstein, the mad scientist is caught off guard by the consequences of his attempt to play God. I use it as an exercise in getting students to locate and elaborate on textual evidence (a skill most lacking in their essays). Check out my study guide:

Get your kids reading and thinking in the coming school year with a dose of good old fashioned horror!

Monday, June 4, 2018

Feeling Grateful for Another Great Year

The End of the Year is a Bag of Mixed Emotions

Here it is June again, the end of another school year--a time to reflect on what went right in the classroom, what promoted effective learning, and what I still need to change.

I feel so grateful for the opportunity to share my passion for language and literature with (generally) open-minded and capable young people. For some kids, reading can be such a struggle, grammar and writing such a chore--but hopefully not for mine. It's all about the passion that you bring to your material and the spirit of compassion with which you delivery it. I have high expectations of my students--we tackle complex texts and work with the subtleties of language--but they always come through for me. Some are motivated by the challenge or the love of the subject, as I was at their age, but many are pulled along and buoyed by the current of the teacher's love and energy. You have to make it relevant, achievable, and yes, fun, for young adolescents. I generally choose classic novels for class texts (I eschew the District's textbook collection of uninteresting and unliterary bits and pieces, truncated and bowdlerized as they are), but I lead students to recognize in them themes that apply to their own lives and the real world around them and provide the skills and guidance that makes them accessible. This year, we read 1984 and Fahrenheit 451, and my students looked around themselves and realized, "yeah, this looks eerily familiar." Good literature, made relevant, illuminates our experiences and opens up new worlds and new possibilities to us. That's what I try to give my students every day. I think I'm on the right track: I received this note the day after school ended from a young man whom I thought wasn't all that engaged:

Dear Mr. Felt,

This is what makes it all worthwhile for me--knowing that I've made a genuine impact on a young person's life. For all the hassle, administrative pettiness, low pay, unreasonable parents, and mindless paperwork, this is why I stay in the profession.

The End of the Year is a Bag of Mixed Emotions

Here it is June again, the end of another school year--a time to reflect on what went right in the classroom, what promoted effective learning, and what I still need to change.

Dear Mr. Felt,

I would like to thank you for teaching me this year. You were an amazing teacher and your class was one of my favorites. You introduced me to timeless, classic novels that I wouldn't have picked out myself but learned much from and really enjoyed reading. My writing, vocabulary, and reading comprehension skills have all improved greatly because of you. I have purchased Edith Hamilton's Mythology per your recommendation and plan to read it along with study the remaining vocabulary in my workbook over the summer. I really appreciate your passion - your love of teaching is unmistakable! Thank you so much for all you've done for me and my education this year.

Sincerely,

Dylan

This is what makes it all worthwhile for me--knowing that I've made a genuine impact on a young person's life. For all the hassle, administrative pettiness, low pay, unreasonable parents, and mindless paperwork, this is why I stay in the profession.

Tuesday, May 29, 2018

Join the Great American Read!

A Powerful Tool to Inspire Readers of all Ages!

PBS has come out with a great list of America's 100 most beloved novels--how many have you read? Take the quiz! And you and your students can vote on your favorites. But the real gem here for teachers is the great video of brief interviews with readers--ordinary and famous--that creates real excitement about reading these novels and how they impacted other people's lives. Plus, it would be easy to break the 2-hour video up into short 3-5 minute segments to show to class. Too bad that the contest is running mostly over the summer vacation, but nonetheless, this is a great resource!

Check it out: http://www.pbs.org/the-great-american-read/home/

A Powerful Tool to Inspire Readers of all Ages!

PBS has come out with a great list of America's 100 most beloved novels--how many have you read? Take the quiz! And you and your students can vote on your favorites. But the real gem here for teachers is the great video of brief interviews with readers--ordinary and famous--that creates real excitement about reading these novels and how they impacted other people's lives. Plus, it would be easy to break the 2-hour video up into short 3-5 minute segments to show to class. Too bad that the contest is running mostly over the summer vacation, but nonetheless, this is a great resource!

Check it out: http://www.pbs.org/the-great-american-read/home/

Wednesday, May 16, 2018

Up Against the Wall!

Encouraging Reading, Promoting Young Adult Literature

I think that I missed my calling as a librarian (not media specialist, thank you very much--library = books). I love being surrounded by books, the smell of lignin, the touch of paper and binding. I love reading, I love the magic of storytelling, the crafting of other worlds, other lives:

And most of all, I love sharing books with students, watching them discover those other worlds, other lives, discovering the pleasure of curling up with a well-told story full of compelling characters, appreciating the clever and artful use of language. In a world suffused with easy entertainment and immediate gratification, it always surprises me that students, for the most part, still respond to the written word (ok, sometimes the spoken word, but I won't quibble too much over audio books). I don't believe in reluctant readers, only readers who haven't met the right book yet.

I teach middle school, and I am keenly aware that the pressures and demands of high school (not just academics, but driving, dating, working, socializing) means little time available for analog activities like reading books. I feel a tremendous urgency to spark a love of reading and lay down rails of habit that will remain throughout a lifetime. I want to keep students reading, and that means holding them accountable, but the old-fashioned summary book report does nothing to encourage interaction with the text (it does, unfortunately, encourage cheating). Instead, I challenge students to advertise their reading selection by creating posters and book jackets that I display on the walls around school: students are given a creative outlet for interacting with the text, authentically address audience and purpose, and promote literacy school-wide. Win-Win!

Check out some samples from this year's crop of pleasure reading choices:

Encouraging Reading, Promoting Young Adult Literature

I think that I missed my calling as a librarian (not media specialist, thank you very much--library = books). I love being surrounded by books, the smell of lignin, the touch of paper and binding. I love reading, I love the magic of storytelling, the crafting of other worlds, other lives:

The poet's eye, in a fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven,

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen

Turns into shapes, and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Or as Dunsany puts it:

And little he knew of the things that ink may do, how it can mark a dead

man's thought for the wonder of later years, and tell of happenings that

are gone clean away, and be a voice for us out of the dark of time, and

save many a fragile thing from the pounding of heavy ages; or carry to us,

over the rolling centuries, even a song from lips long dead on forgotten

hills.

Or as Dunsany puts it:

And little he knew of the things that ink may do, how it can mark a dead

man's thought for the wonder of later years, and tell of happenings that

are gone clean away, and be a voice for us out of the dark of time, and

save many a fragile thing from the pounding of heavy ages; or carry to us,

over the rolling centuries, even a song from lips long dead on forgotten

hills.

And most of all, I love sharing books with students, watching them discover those other worlds, other lives, discovering the pleasure of curling up with a well-told story full of compelling characters, appreciating the clever and artful use of language. In a world suffused with easy entertainment and immediate gratification, it always surprises me that students, for the most part, still respond to the written word (ok, sometimes the spoken word, but I won't quibble too much over audio books). I don't believe in reluctant readers, only readers who haven't met the right book yet.

I teach middle school, and I am keenly aware that the pressures and demands of high school (not just academics, but driving, dating, working, socializing) means little time available for analog activities like reading books. I feel a tremendous urgency to spark a love of reading and lay down rails of habit that will remain throughout a lifetime. I want to keep students reading, and that means holding them accountable, but the old-fashioned summary book report does nothing to encourage interaction with the text (it does, unfortunately, encourage cheating). Instead, I challenge students to advertise their reading selection by creating posters and book jackets that I display on the walls around school: students are given a creative outlet for interacting with the text, authentically address audience and purpose, and promote literacy school-wide. Win-Win!

Check out some samples from this year's crop of pleasure reading choices:

Wednesday, April 18, 2018

Don't Get Caught Flat!

Reading Scores Continue to Stagnate

A recent article in The Atlantic, "Why American Students Haven't Gotten Better at Reading in 20 Years," caught my eye and got me to thinking about reading instruction in my classroom. According to the most recent report card from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, reading scores continue to remain flat despite the haranguing of legislators, the scapegoating of District administrators, and the consternation of overworked teachers. The money, the pedagogical fads, the constant testing, the sticks and carrots--none have had any significant impact as evidenced on the NAEP graph:

The Atlantic's article suggests that schools and teachers focus too much on isolated comprehension skills and not enough on content; in other words, if students do not have background in what their reading, or if the content of comprehension practice texts varies randomly, then readers are unable to fill in knowledge gaps. "Daniel Willingham, a psychology professor at the University of Virginia who writes about the science behind reading comprehension [...] explained that whether or not readers understand a text depends far more on how much background knowledge and vocabulary they have relating to the topic than on how much they’ve practiced comprehension skills."

One suggestion, then, is to center instruction around content domains--Colonial America, the Civil War and Reconstruction, Great Depression and New Deal, etc., spending a semester or even the whole year on a limited topic; each grade level would be responsible for a specific domain. Pretty cool idea, but this is 'Murica and we're not going to let any centralized gubment tell us what to teach! Thematic units, either designed by textbook companies (yuck) or teachers are one way to increase depth of knowledge. It's a fair amount of work locating complementing informational and literary texts: primary sources, historical documents, essays, prose fiction in varied genres, but doing so provides an immersive reading experience that is likely (so the research says) to be more effective in promoting literacy.

Such a thematic approach leads into The Atlantic's next point: developing readers must wrestle with grade-level, complex text that challenges them. New words, complicated syntax, novel ideas--it's ok to struggle. That's where learning happens. "Timothy Shanahan [emeritus professor at the University of Illinois and the author or editor of over 200 publications on literacy] cites recent research indicating that students actually learn more from reading texts that are considered too difficult for them—in other words, those with more than a handful of words and concepts a student doesn't understand. What struggling students need is guidance from a teacher in how to make sense of texts designed for kids at their respective grade levels—the kinds of texts those kids may otherwise see only on standardized tests, when they have to grapple with them on their own." The teacher's role then becomes one of guide, helping students navigate unfamiliar and rocky terrain.

At the middle and high school level, language arts teachers and social studies teachers (science teachers, too?) could work together to craft thematic units and select complementing texts, sharing the responsibility for building knowledge and crafting authentic opportunities for applied literacy.

Throwing my own two-cents' worth: suggestions a for civil rights unit, developing historical knowledge and empathy for the plight of the oppressed in Jim Crow America. First, Billie Holiday's extraordinary "Strange Fruit":

You'll have to copy & paste the links for the resources below (I can't see to work out how to hot link them--sorry):

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Unsung-Heroes-More-Non-Fiction-Readings-from-the-Civil-Rights-Era-819934

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Unsung-Heroes-More-Non-Fiction-Readings-from-the-Civil-Rights-Era-819934

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Black-Voices-pre-Civil-Rights-Era-reading-practice-with-objective-assessments-295418https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Non-Fiction-Readings-from-the-Civil-Rights-Era-texts-Objective-Assessments-297522

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Black-Voices-pre-Civil-Rights-Era-reading-practice-with-objective-assessments-295418https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Non-Fiction-Readings-from-the-Civil-Rights-Era-texts-Objective-Assessments-297522

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/To-Kill-A-Mockingbird-objective-assessment-and-instructional-notes-293640

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/To-Kill-A-Mockingbird-objective-assessment-and-instructional-notes-293640

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Their-Eyes-Were-Watching-God-study-guide-and-objective-assessment-293794

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Their-Eyes-Were-Watching-God-study-guide-and-objective-assessment-293794

Reading Scores Continue to Stagnate

A recent article in The Atlantic, "Why American Students Haven't Gotten Better at Reading in 20 Years," caught my eye and got me to thinking about reading instruction in my classroom. According to the most recent report card from the National Assessment of Educational Progress, reading scores continue to remain flat despite the haranguing of legislators, the scapegoating of District administrators, and the consternation of overworked teachers. The money, the pedagogical fads, the constant testing, the sticks and carrots--none have had any significant impact as evidenced on the NAEP graph:

The Atlantic's article suggests that schools and teachers focus too much on isolated comprehension skills and not enough on content; in other words, if students do not have background in what their reading, or if the content of comprehension practice texts varies randomly, then readers are unable to fill in knowledge gaps. "Daniel Willingham, a psychology professor at the University of Virginia who writes about the science behind reading comprehension [...] explained that whether or not readers understand a text depends far more on how much background knowledge and vocabulary they have relating to the topic than on how much they’ve practiced comprehension skills."

One suggestion, then, is to center instruction around content domains--Colonial America, the Civil War and Reconstruction, Great Depression and New Deal, etc., spending a semester or even the whole year on a limited topic; each grade level would be responsible for a specific domain. Pretty cool idea, but this is 'Murica and we're not going to let any centralized gubment tell us what to teach! Thematic units, either designed by textbook companies (yuck) or teachers are one way to increase depth of knowledge. It's a fair amount of work locating complementing informational and literary texts: primary sources, historical documents, essays, prose fiction in varied genres, but doing so provides an immersive reading experience that is likely (so the research says) to be more effective in promoting literacy.

Such a thematic approach leads into The Atlantic's next point: developing readers must wrestle with grade-level, complex text that challenges them. New words, complicated syntax, novel ideas--it's ok to struggle. That's where learning happens. "Timothy Shanahan [emeritus professor at the University of Illinois and the author or editor of over 200 publications on literacy] cites recent research indicating that students actually learn more from reading texts that are considered too difficult for them—in other words, those with more than a handful of words and concepts a student doesn't understand. What struggling students need is guidance from a teacher in how to make sense of texts designed for kids at their respective grade levels—the kinds of texts those kids may otherwise see only on standardized tests, when they have to grapple with them on their own." The teacher's role then becomes one of guide, helping students navigate unfamiliar and rocky terrain.

At the middle and high school level, language arts teachers and social studies teachers (science teachers, too?) could work together to craft thematic units and select complementing texts, sharing the responsibility for building knowledge and crafting authentic opportunities for applied literacy.

Throwing my own two-cents' worth: suggestions a for civil rights unit, developing historical knowledge and empathy for the plight of the oppressed in Jim Crow America. First, Billie Holiday's extraordinary "Strange Fruit":

You'll have to copy & paste the links for the resources below (I can't see to work out how to hot link them--sorry):

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Unsung-Heroes-More-Non-Fiction-Readings-from-the-Civil-Rights-Era-819934

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Unsung-Heroes-More-Non-Fiction-Readings-from-the-Civil-Rights-Era-819934 https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Black-Voices-pre-Civil-Rights-Era-reading-practice-with-objective-assessments-295418https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Non-Fiction-Readings-from-the-Civil-Rights-Era-texts-Objective-Assessments-297522

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Black-Voices-pre-Civil-Rights-Era-reading-practice-with-objective-assessments-295418https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Non-Fiction-Readings-from-the-Civil-Rights-Era-texts-Objective-Assessments-297522 https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/To-Kill-A-Mockingbird-objective-assessment-and-instructional-notes-293640

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/To-Kill-A-Mockingbird-objective-assessment-and-instructional-notes-293640 https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Their-Eyes-Were-Watching-God-study-guide-and-objective-assessment-293794

https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/Their-Eyes-Were-Watching-God-study-guide-and-objective-assessment-293794Tuesday, April 10, 2018

Visual Literacy is a Thing

Reading Images is as Important as Reading Words

Alternative literacies are becoming increasingly relevant in our image-driven, fast-paced media world. Students are going to encounter texts that are heavily (perhaps entirely) graphic in nature, and they need the skills to accurately process the message of such tests. We see this reflected to some extent now on state assessments and standardized tests in the form of the (occasional) chart or map; I think the trend of asking students to interpret graphic information is likely to increase in the near future.

Political cartoons are a great place to start for fun, thought-provoking lessons that can be accomplished in just a few minutes--perhaps as a bell-ringer. Of course, you might want to stay away from hot current events, as there's a possibility, in these divided times, of angering some far-right or far-left parent, and who needs that kind of headache? Perhaps stick to historical political cartoons--they might be safer:

Ask students to describe what they see--what does each element represent? What is the message the illustrator is trying to convey? What persuasive techniques is she using? A nifty resource on-line is History Skills -- definitely worth checking out. Of course, our colleagues in the Social Studies department can be a tremendous help in instructing and practicing the interpretation of graphic information: maps, charts, graphs; by all means, enlist their help and offer to collaborate.

But we're English teachers, and our hearts are set on fire not by politics but by great stories artfully told. Well, there are some great ways to incorporate visual literacy into the literature curriculum. The proliferation of graphic novels, not as substitutes for original written texts but as original narratives standing on their own literary merits, is widely available (although pretty pricey on an educator's budget). Check out Compass South and its sequel Knife's Edge by Hope Larson and illustrated by Rebecca Mock (my former student 💖)--a wonderful story full of adventure and great story telling sure to engage the most reluctant reader (grades 5-8):

Reading Images is as Important as Reading Words

Alternative literacies are becoming increasingly relevant in our image-driven, fast-paced media world. Students are going to encounter texts that are heavily (perhaps entirely) graphic in nature, and they need the skills to accurately process the message of such tests. We see this reflected to some extent now on state assessments and standardized tests in the form of the (occasional) chart or map; I think the trend of asking students to interpret graphic information is likely to increase in the near future.

Political cartoons are a great place to start for fun, thought-provoking lessons that can be accomplished in just a few minutes--perhaps as a bell-ringer. Of course, you might want to stay away from hot current events, as there's a possibility, in these divided times, of angering some far-right or far-left parent, and who needs that kind of headache? Perhaps stick to historical political cartoons--they might be safer:

Ask students to describe what they see--what does each element represent? What is the message the illustrator is trying to convey? What persuasive techniques is she using? A nifty resource on-line is History Skills -- definitely worth checking out. Of course, our colleagues in the Social Studies department can be a tremendous help in instructing and practicing the interpretation of graphic information: maps, charts, graphs; by all means, enlist their help and offer to collaborate.

But we're English teachers, and our hearts are set on fire not by politics but by great stories artfully told. Well, there are some great ways to incorporate visual literacy into the literature curriculum. The proliferation of graphic novels, not as substitutes for original written texts but as original narratives standing on their own literary merits, is widely available (although pretty pricey on an educator's budget). Check out Compass South and its sequel Knife's Edge by Hope Larson and illustrated by Rebecca Mock (my former student 💖)--a wonderful story full of adventure and great story telling sure to engage the most reluctant reader (grades 5-8):

The Invention of Hugo Cabret is a sumptuously illustrated novel that I fell in love with--beautiful art, compelling narrative, and a gateway to a lost world of silent film making and automatons. Just brilliant!!

Another great novel to share with students is Art Spiegelman's Maus, a Holocaust allegory that really humanizes the harrowing events that ordinary individuals lived through (grades 7-10). This powerful narrative does much of its story telling through the use of visual elements, so it's a great way to help students develop their visual literacy. I put together a study guide that focuses in on the graphic analysis skills that students need to master. Check it out:

Gary Schmidt's Okay for Now is a wonderful hybrid: a great young adult novel which revolves around the amazing and awesome bird paintings of John Audubon. Each chapter begins with one of Audubon's paintings and really focuses on the emotional quality of the painting; the action of the chapter mirrors the painting. Unfortunately, the images in the book, at the beginning of each chapter, are pretty poor (and in black and white). I wanted students to see them clearly, and to make the connections between painting and chapter, so I created an assignment that allows them to do just that. But then, to take it further, I included several more Audubon paintings not in the novel and asked students to carefully analyze what they saw, describe it, and impart an emotional mood to the painting. Students and I really enjoyed this (grades 5-8):

Thursday, April 5, 2018

Listening for Fun and Profit

Addressing Listening Standards on State Assessments

Who doesn't love kicking back and listening to a good story? I know I sure do! I think the rise of audio books is attributable to our love for hearing a compelling story well told (that, plus the fact that we're always on the go, too busy to sit down with a book). When we're studying a novel, I don't fret too much if students are listening to it on audio rather than reading the text (although I encourage them to follow along in the text as they listen). I'm not teaching 14 year olds how to sound out words and interpret the squiggles on the page--we've moved beyond reading to analysis and evaluation of plot, setting, language, and character.

The increasing popularity of non-print media has, I think, driven the move to assess listening skills on state and Common Core tests. Unfortunately, of what I've seen on our Florida test, the assessment tasks are neither particularly rigorous nor relevant. Students are usually presented with some banal and forgettable news report, and asked the most general of questions. Certainly, they don't have to remember much in the way of detail. But that doesn't mean listening skills should be ignored--being able to appreciate and glean information from listening is a useful life skill. I enjoy reading aloud to students and they respond with pleasure (they seem to be impressed by my oral interp skills--lol). I read Capote's A Christmas Memory and Margery William's Velveteen Rabbit (funny, there must be some mold or something in my copies of these stories--I'm usually pretty snuffly by the end). Since I'm doing the reading, it's easy for me to stop and ask questions or clarify odd language, then we can discuss the whole story at the end.

And of course, Poe and Kipling make wonderful read-alouds. I made some active-listening handouts to go with The Tell-Tale Heart and The Elephant's Child (one of Kipling's Just-So Stories). Each handout (just one page, front and back) focuses the listener's attention on important literary elements of the story, rather than factual recall, trivia questions about the plot. I was pleased at the students' response--they found both the stories and the activity engaging. Click onto the image below to read a description of my assignment and how to purchase it.

|

Informational text is also fair game for active listening. NPR's various news programs (Morning Edition, All Things Considered, Fresh Air, etc) provide audio texts of 3-5 minutes that are perfect for asking students to listen for main idea, cause and effect, reasons, and examples. The "This I Believe" series provides fantastic spoken essays covering a myriad of topics by famous and ordinary folk (I loved and used the Ben Carson essay for many years, until I found out what an ass he really is).

Informational text is also fair game for active listening. NPR's various news programs (Morning Edition, All Things Considered, Fresh Air, etc) provide audio texts of 3-5 minutes that are perfect for asking students to listen for main idea, cause and effect, reasons, and examples. The "This I Believe" series provides fantastic spoken essays covering a myriad of topics by famous and ordinary folk (I loved and used the Ben Carson essay for many years, until I found out what an ass he really is).Tuesday, April 3, 2018

Orphaned Words?

Students Adopt a Word!

Here's this cool new gizmo for printing a word onto (what looks like a) washer and making that into a bracelet or necklace. I think the intent is to be mindful and use it for some sort of gratitude exercise. But what if each student chose a cool, exotic word (cacatory, bamboozle, diffibulate, egrote) that's fast fading from the lexicon, and adopt it? Promise to use it and bring it back to the vernacular? How cool would that be? Thoughts? From MyIntent:

Students Adopt a Word!

Here's this cool new gizmo for printing a word onto (what looks like a) washer and making that into a bracelet or necklace. I think the intent is to be mindful and use it for some sort of gratitude exercise. But what if each student chose a cool, exotic word (cacatory, bamboozle, diffibulate, egrote) that's fast fading from the lexicon, and adopt it? Promise to use it and bring it back to the vernacular? How cool would that be? Thoughts? From MyIntent:

Monday, April 2, 2018

Show Your True Colors!

Paint a Chalk Wall and Inspire Your Students

I have had such a fun time with our hallway chalk wall--a great outlet for my creative side. At the intersection of two wide hallways (interior), there was a large expanse of emptiness, and I thought, what can I do with this space? I didn't want to paint a mural--I wanted something I could change with the seasons and what we're currently studying. What I found was chalkboard paint!

I tried both the Rustoleum and the Valspar, and liked the Valspar better--it seemed to cover better. I needed three coats in order to get a smooth, uniform surface. One can ($10) gave me two solid coats for a 6' x 6' area. I use the regular sidewalk chalk you find at Michael's.

I usually do two boards every month or so. Last month I did a Martin Luther King Jr quote for Black history month:

Paint a Chalk Wall and Inspire Your Students

I have had such a fun time with our hallway chalk wall--a great outlet for my creative side. At the intersection of two wide hallways (interior), there was a large expanse of emptiness, and I thought, what can I do with this space? I didn't want to paint a mural--I wanted something I could change with the seasons and what we're currently studying. What I found was chalkboard paint!

I tried both the Rustoleum and the Valspar, and liked the Valspar better--it seemed to cover better. I needed three coats in order to get a smooth, uniform surface. One can ($10) gave me two solid coats for a 6' x 6' area. I use the regular sidewalk chalk you find at Michael's.

I usually do two boards every month or so. Last month I did a Martin Luther King Jr quote for Black history month:

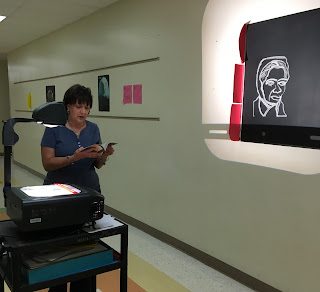

I use an old-fashioned overhead projector since I have 0% artistic talent. I copy an image onto transparency film (I still have a box of it from the bad old days, pre-computer document reader). Here's my colleague working on her history quote board:

Great fun! And the kids really seem to respond to it. Pro tip: situate your chalk wall in an area where the kids are not prone to rubbing against the wall. Here are some more examples:

Monday, March 26, 2018

It’s Almost State-Assessment Testing

Time!

Time to Pluck the low-hanging Fruit

With just a few weeks before we begin high-stakes state

testing, how can teachers most effectively and productively utilize the little

classroom time left to us? Here in

Florida, and I suspect on most Common Core-based assessments, the editing tasks

are ripe and ready to harvest. These

tasks—usually a paragraph or a number of sentences with grammatical, spelling,

or punctuation errors to be corrected—are quick and easy items to instruct and

are most likely to bear results on the test.

By picking up a few points on these relatively easy items, students on

the border between one reading level and

the next higher may be able to make the leap.

The common grammatical errors that students are likely to

see are subject/verb agreement, correct use of relative pronouns (that vs.

who), and incorrect tense shifts. Exotic

punctuation like dashes and colons are likely targets in mechanics. And spelling—well, that’s a bit tougher to

improve quickly, but concentrate on common mistakes like there/they’re/their

and its/it’s.

If you’re looking for quick and cheap (but also effective

and engaging) resources, Feltopia Press offers the first unit of Problem Words—Pronouns and Contractions

for free; this is the first unit in a workbook series on often-confused words

like homonyms and contractions, and comes with a PowerPoint and practice

exercises. You might also want to check

out Advanced Punctuation, a

PowerPoint–based activity that covers colons, semicolons, dashes, parentheses,

hyphens, and ellipses.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)